Weavers National Hui 2019

30 October 2019Click here to visit an upgraded version of this blog post on my new website at alibrown.nz.

The 2019 Weavers National Hui, held over four days at Labour weekend at Ngā Hau e Whā National marae in Ōtautahi/Christchurch was a terrific success in my view. Thanks go to the organising group including Ranui Ngarimu and Paula Rigby and the many obliging volunteers, who put together a weekend of weaving, knowledge sharing, forums and visits to sites of interest. The delicious food served up by Te Runanga o Nga Maata Waka completed the enjoyable experience.

The 2019 Weavers National Hui, held over four days at Labour weekend at Ngā Hau e Whā National marae in Ōtautahi/Christchurch was a terrific success in my view. Thanks go to the organising group including Ranui Ngarimu and Paula Rigby and the many obliging volunteers, who put together a weekend of weaving, knowledge sharing, forums and visits to sites of interest. The delicious food served up by Te Runanga o Nga Maata Waka completed the enjoyable experience.

One of the highlights was the presentation of two groups studying Te Rā: The Māori sail, which is the only known Māori sail left in existence and is held by the British Museum. One group is studying the sail from a practical weaver’s approach, working out the weaving techniques used to weave Te Rā. With this knowledge they hope to recreate a traditional sail. At the hui, members of the group were weaving samples using very fine weaving strips. The techniques include open-weave sections that allow the wind through the sails. Follow their progress on Facebook. The other group, looking from a scientific perspective, used a polarised light microscope to compare tiny specimens taken from Te Rā to a set of identified reference materials. They confirmed that the material that Te Rā is made from is actually harakeke, Phormium tenax, that is, New Zealand Flax. Follow their progress here.

One of the highlights was the presentation of two groups studying Te Rā: The Māori sail, which is the only known Māori sail left in existence and is held by the British Museum. One group is studying the sail from a practical weaver’s approach, working out the weaving techniques used to weave Te Rā. With this knowledge they hope to recreate a traditional sail. At the hui, members of the group were weaving samples using very fine weaving strips. The techniques include open-weave sections that allow the wind through the sails. Follow their progress on Facebook. The other group, looking from a scientific perspective, used a polarised light microscope to compare tiny specimens taken from Te Rā to a set of identified reference materials. They confirmed that the material that Te Rā is made from is actually harakeke, Phormium tenax, that is, New Zealand Flax. Follow their progress here.

A large part of the hui was spent sharing basic and advanced weaving ideas and techniques. For example, a kuia showed Chiu, pictured above, how to weave a sun-visor hat, potae, and I showed a weaver from Tāmaki-makau-rau/Auckland how to make a neat even finish on the top edge of her first waikawa.

Several people commented on the koru pendant I designed a few years ago and was wearing, so I showed them how it’s made. One kuia was interested to weave this pendant as she was weaving items for tourists and thought the pendant was small and light and is easy to carry in luggage. If you’d like to make one yourself, check out my blog post “Weaving Jewellery” where you’ll find instructions for that pendant and other pendants made using the curved four plait.

Several people commented on the koru pendant I designed a few years ago and was wearing, so I showed them how it’s made. One kuia was interested to weave this pendant as she was weaving items for tourists and thought the pendant was small and light and is easy to carry in luggage. If you’d like to make one yourself, check out my blog post “Weaving Jewellery” where you’ll find instructions for that pendant and other pendants made using the curved four plait.

This year, the exhibition at National Hui celebrated the weaver and kete — a kete made by the attendee, or one brought, gifted or inherited. The stunning display of kete in this exhibition showcased the wide variety of designs, patterns and weaving techniques that encompass the weaving of the past and present. I don’t have permission to use images of the ketes in the exhibition, apart from this one which is the first kete whakairo, or patterned kete, I wove. The pattern is Koeaea and represents whitebait swimming.

This year, the exhibition at National Hui celebrated the weaver and kete — a kete made by the attendee, or one brought, gifted or inherited. The stunning display of kete in this exhibition showcased the wide variety of designs, patterns and weaving techniques that encompass the weaving of the past and present. I don’t have permission to use images of the ketes in the exhibition, apart from this one which is the first kete whakairo, or patterned kete, I wove. The pattern is Koeaea and represents whitebait swimming.

The National Weavers Hui is held every two years and it’s well worth going to. The next one in 2021 will be held in Otaki and I look forward to meeting up with old and new weaving friends there.

My thanks to the ©Trustees of the British Museum for permission to use the image of Te Rā on this post.

© Alison Marion Brown 2019.

I’m pleased to say that my online instructions for Weaving a Flower from New Zealand flax are now available on this website in te reo Māori as

I’m pleased to say that my online instructions for Weaving a Flower from New Zealand flax are now available on this website in te reo Māori as  I’ve learned quite a lot of Māori words through my work with flax weaving over the years and found that the combination of my love of weaving with my learning of te reo Māori gives a synergy to my ability to learn. I’m glad to say that I can now string some sentences together that relate to weaving. For example, “E hia ngā whenu?” when I want to know the number of strips for weaving a certain piece, or “He aha te tae o te waitae?” when I want to know the colour of a dye. By the way, I didn’t record the name of the dye I used in this kete whakairo, which I do these days as it’s a very useful source of information.

I’ve learned quite a lot of Māori words through my work with flax weaving over the years and found that the combination of my love of weaving with my learning of te reo Māori gives a synergy to my ability to learn. I’m glad to say that I can now string some sentences together that relate to weaving. For example, “E hia ngā whenu?” when I want to know the number of strips for weaving a certain piece, or “He aha te tae o te waitae?” when I want to know the colour of a dye. By the way, I didn’t record the name of the dye I used in this kete whakairo, which I do these days as it’s a very useful source of information.  At my last flax weaving workshop, in addition to showing people how to weave small baskets and large containers, I invited more experienced weavers to learn how to make an open-weave basket — kupenga kete — and four people took up the offer. I’d woven my kupenga kete a few years ago and the questions Beryl, Kath, Gill and Oz asked while weaving their baskets reminded me of the things that need to be worked out as the basket is woven and I thought I’d share this information. When gathering flax for this basket, choose firm flax as the strips need to be quite firm to retain the shape of the open weave in the basket. The basket I’m using to illustrate this post is woven with 64 strips that are 0.5 cm wide, with fine fibre, or muka ends. The number of strips required needs to be divisable by 8.

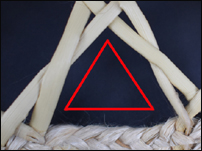

At my last flax weaving workshop, in addition to showing people how to weave small baskets and large containers, I invited more experienced weavers to learn how to make an open-weave basket — kupenga kete — and four people took up the offer. I’d woven my kupenga kete a few years ago and the questions Beryl, Kath, Gill and Oz asked while weaving their baskets reminded me of the things that need to be worked out as the basket is woven and I thought I’d share this information. When gathering flax for this basket, choose firm flax as the strips need to be quite firm to retain the shape of the open weave in the basket. The basket I’m using to illustrate this post is woven with 64 strips that are 0.5 cm wide, with fine fibre, or muka ends. The number of strips required needs to be divisable by 8. The basket is started by adding two sets of two strips each side, each time i.e. 8 strips altogether, into the plait at set intervals in order to create the diamond pattern. It makes a difference how fat the plait is as to how often the strips are added in. If the fibre ends have been scraped down to fine fibre, which makes a finer plait, then more plaiting is required between each set of strips. If the fibre ends still retain some of the green fleshy part of the flax, then the plait may be quite fat, and the sets of strips will need to be added more frequently. This illustration shows six rows of plaiting between each addition of strips. (As the illustration is from a completed dried basket it is showing already-woven strips rather than green strips, as yours will be, when you add them to the plait.)

The basket is started by adding two sets of two strips each side, each time i.e. 8 strips altogether, into the plait at set intervals in order to create the diamond pattern. It makes a difference how fat the plait is as to how often the strips are added in. If the fibre ends have been scraped down to fine fibre, which makes a finer plait, then more plaiting is required between each set of strips. If the fibre ends still retain some of the green fleshy part of the flax, then the plait may be quite fat, and the sets of strips will need to be added more frequently. This illustration shows six rows of plaiting between each addition of strips. (As the illustration is from a completed dried basket it is showing already-woven strips rather than green strips, as yours will be, when you add them to the plait.) To check if the length of plait in between each set of strips is right, hold up two strips from each set together at the top to show the shape of the diamond. If the strips are too far apart, the diamond will be too big, so reduce the number of plaits between each set of strips addition.

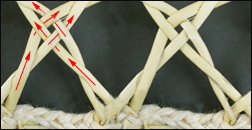

To check if the length of plait in between each set of strips is right, hold up two strips from each set together at the top to show the shape of the diamond. If the strips are too far apart, the diamond will be too big, so reduce the number of plaits between each set of strips addition. Once all of the strips are added in and the plait is tied off, then weave the sets of strips on one side to start the pattern. The strips from each set of four are firstly woven together by weaving the right strip over the left strip in both sets of two. Then weave the second strip over the third strip which sets them in the right place for the pattern. Peg in place and repeat for all the sets of strips on one side. The two strips left at each end are used to weave the corners.

Once all of the strips are added in and the plait is tied off, then weave the sets of strips on one side to start the pattern. The strips from each set of four are firstly woven together by weaving the right strip over the left strip in both sets of two. Then weave the second strip over the third strip which sets them in the right place for the pattern. Peg in place and repeat for all the sets of strips on one side. The two strips left at each end are used to weave the corners. Cross the two strips (I always cross the strips in the same direction as it helps to keep the pattern looking well-made and attractive), and then take the left set of crossed strips from the first set on the left and the right set of crossed strips from the adjacent set and weave the two sets of strips through each other in under/over — taki tahi — weave. Go to the next four strips and repeat this across to the end of the plait on this side. Look at the half diamonds that have been created along this first row and make sure they are basically the same size and shape. If they aren’t adjust the tension to make them as similar as possible.

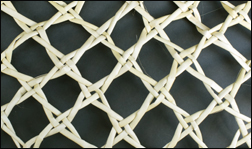

Cross the two strips (I always cross the strips in the same direction as it helps to keep the pattern looking well-made and attractive), and then take the left set of crossed strips from the first set on the left and the right set of crossed strips from the adjacent set and weave the two sets of strips through each other in under/over — taki tahi — weave. Go to the next four strips and repeat this across to the end of the plait on this side. Look at the half diamonds that have been created along this first row and make sure they are basically the same size and shape. If they aren’t adjust the tension to make them as similar as possible.  Repeat this crossing of two strips and then weaving four strips together across the side two more times and there will now be full diamond shapes created with the weaving. Peg in place and repeat on the other side. Fold both sides up together and then weave the corner together with the two strips left at the end of each side. Before weaving any higher, secure the ends of the plait inside the kete with a tie so that they lie flat and neatly along the inside of the plait.

Repeat this crossing of two strips and then weaving four strips together across the side two more times and there will now be full diamond shapes created with the weaving. Peg in place and repeat on the other side. Fold both sides up together and then weave the corner together with the two strips left at the end of each side. Before weaving any higher, secure the ends of the plait inside the kete with a tie so that they lie flat and neatly along the inside of the plait. Once the sides are completed to the height you want, finish with the four weave crossing and peg the strips in place. Comb the ends out into fibre and plait these together for the top edge. To do this, I use a set of three narrow flax strips tied together to start the plait and then bring each bunch of fibres from the end of each strip into the plait as in French plaiting. See pages 78-82 in my book

Once the sides are completed to the height you want, finish with the four weave crossing and peg the strips in place. Comb the ends out into fibre and plait these together for the top edge. To do this, I use a set of three narrow flax strips tied together to start the plait and then bring each bunch of fibres from the end of each strip into the plait as in French plaiting. See pages 78-82 in my book  There are different ways to finish the plait. For example, the end of the plait can be threaded through to the inside of the rim and tied in place or the plait can be lengthened to make a decorative finish. The ends can be left on or cut off as in Gill’s kete illustrated here. It was good to see others weaving this basket as it highlighted the things to think about and observe in the weaving. I hope you find this useful when you weave your own kupenga kete, and do send me photos of your finished weaving. I’d love to see them and share them here.

There are different ways to finish the plait. For example, the end of the plait can be threaded through to the inside of the rim and tied in place or the plait can be lengthened to make a decorative finish. The ends can be left on or cut off as in Gill’s kete illustrated here. It was good to see others weaving this basket as it highlighted the things to think about and observe in the weaving. I hope you find this useful when you weave your own kupenga kete, and do send me photos of your finished weaving. I’d love to see them and share them here.